Dask Kubernetes Operator

By Jacob Tomlinson (NVIDIA)

We are excited to announce that the Dask Kubernetes Operator is now generally available 🎉!

Notable new features include:

- Dask Clusters are now native custom resources

- Clusters can be managed with

kubectlor the Python API - Cascaded deletions allow for proper teardown

- Multiple worker groups enable heterogenous/tagged deployments

- DaskJob: running dask workloads with K8s batched job infrastructure

- Clusters can be reused between different Python processes

- Autoscaling is handled by a custom Kubernetes controller instead of the user code

- Scheduler and worker Pods and Services are fully configurable

$ kubectl get daskcluster

NAME AGE

my-cluster 4m3s

$ kubectl get all -A -l dask.org/cluster-name=my-cluster

NAMESPACE NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

default pod/my-cluster-default-worker-22bd39e33a 1/1 Running 0 3m43s

default pod/my-cluster-default-worker-5f4f2c989a 1/1 Running 0 3m43s

default pod/my-cluster-default-worker-72418a589f 1/1 Running 0 3m43s

default pod/my-cluster-default-worker-9b00a4e1fd 1/1 Running 0 3m43s

default pod/my-cluster-default-worker-d6fc172526 1/1 Running 0 3m43s

default pod/my-cluster-scheduler 1/1 Running 0 4m21s

NAMESPACE NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE

default service/my-cluster-scheduler ClusterIP 10.96.33.67 <none> 8786/TCP,8787/TCP 4m21s

At the start of 2022 we began the large undertaking of rewriting the dask-kubernetes package in the operator pattern. This design pattern has become very popular in the Kubernetes community with companies like Red Hat building their whole Kubernetes offering Openshift around it.

What is an operator?

If you’ve spent any time in the Kubernetes community you’ll have heard the term operator being thrown around seen projects like Golang’s Operator Framework being used to deploy modern applications.

At it’s core an operator is made up of a data structure for describing the thing you want to deploy (in our case a Dask cluster) and a controller which does the actual deploying. In Kubernetes the templates for these data structures are called Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs) and allow you to extend the Kubernetes API with new resource types of your own design.

For dask-kubernetes we have created a few CRDs to describe things like Dask clusters, groups of Dask workers, adaptive autoscalers and a new Dask powered batch job.

We also built a controller using kopf that handles watching for changes to any of these resources and creates/updates/deletes lower level Kubernetes resources like Pods and Services.

Why did we build this?

The original implementation of dask-kubernetes was started shortly after Kubernetes went 1.0 and before any established design patterns had emerged. Its model was based on spawning Dask workers as subprocesses, except those subprocesses are Pods running in Kubernetes. This is the same way dask-jobqueue launches workers as individual job scheduler allocations or dask-ssh opens many SSH connections to various machines.

Over time this has been refactored, rewritten and extended multiple times. One long-asked-for change was to also place the Dask scheduler inside the Kubernetes cluster to simplify scheduler-worker communication and network connectivity. Naturally this lead to more feature requests around configuring the scheduler service and having more control over the cluster. As we extended more and more the original premise of spawning worker subprocesses on a remote system became less helpful.

The final straw in the original design was folks asking for the ability to leave a cluster running and come back to it later. Either to reuse a cluster between separate jobs, or just different stages in a multi-stage pipeline. The premise of spawning subprocesses leads to an assumption that the parent process will be around for the lifetime of the cluster which makes it a reasonable place to hold state such as the template for launching new workers when scaling up. We attempted to implement this feature but it just wasn’t possible with the current design. Moving to a model where the parent process can die and new processes can pick up means that state needs to be moved elsewhere and things were too entangled to successfully pull this out.

The classic implementation that had served us well for so long was creaking and becoming increasingly difficult to modify and maintain. The time had come to pay down our technical debt by rebuilding from scratch under a new model, the operator pattern.

In this new model a Dask cluster is an abstract object that exists within a Kubernetes cluster. We use custom resources to store the state for each cluster and a custom controller to map that state onto reality by creating the individual components that make up the cluster. Want to scale up your cluster? Instead of having some Python code locally that spawns a new Pod on Kubernetes we just modify the state of the Dask cluster resource to specify the desired number of workers and the controller handles adding/removing Pods to match.

New features

While our primary goal was allowing cluster reuse between Python processes and paying down technical debt switching to the operator pattern has allowed us to add a bunch of nice new features. So let’s explore those.

Python or YAML API

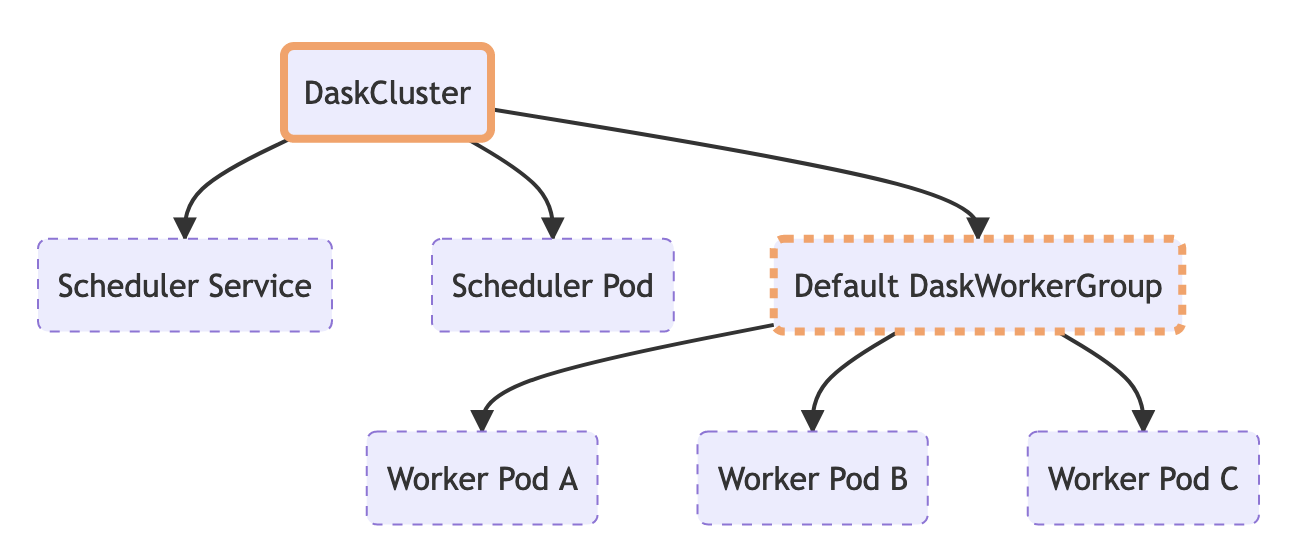

With our new implementation we create Dask clusters by creating a DaskCluster resource on our Kubernetes cluster. The controller sees this appear and spawns child resources for the scheduler, workers, etc.

We modify our cluster by editing the DaskCluster resource and our controller reacts to those changes and updates the child resources accordingly.

We delete our cluster by deleting the DaskCluster resource and Kubernetes handles the rest (see the next section on cascade deletion).

By storing all of our state in the resource and all of our logic in the controller this means the KubeCluster class is now much simpler. It’s actually so simple that it is entirely optional.

The primary purpose of the KubeCluster class now is to provide a nice clean API for creating/scaling/deleting your clusters in Python. It can take a small number of keyword arguments and generate all of the YAML to submit to Kubernetes.

from dask_kubernetes.operator import KubeCluster

cluster = KubeCluster(name="my-cluster", n_workers=3, env={"FOO": "bar"})

The above snippet creates the following resource.

apiVersion: kubernetes.dask.org/v1

kind: DaskCluster

metadata:

name: my-cluster

spec:

scheduler:

service:

ports:

- name: tcp-comm

port: 8786

protocol: TCP

targetPort: tcp-comm

- name: http-dashboard

port: 8787

protocol: TCP

targetPort: http-dashboard

selector:

dask.org/cluster-name: my-cluster

dask.org/component: scheduler

type: ClusterIP

spec:

containers:

- args:

- dask-scheduler

- --host

- 0.0.0.0

env:

- name: FOO

value: bar

image: ghcr.io/dask/dask:latest

livenessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /health

port: http-dashboard

initialDelaySeconds: 15

periodSeconds: 20

name: scheduler

ports:

- containerPort: 8786

name: tcp-comm

protocol: TCP

- containerPort: 8787

name: http-dashboard

protocol: TCP

readinessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /health

port: http-dashboard

initialDelaySeconds: 5

periodSeconds: 10

resources: null

worker:

cluster: my-cluster

replicas: 3

spec:

containers:

- args:

- dask-worker

- --name

- $(DASK_WORKER_NAME)

env:

- name: FOO

value: bar

image: ghcr.io/dask/dask:latest

name: worker

resources: null

If I want to scale up my workers to 5 I can do this in Python.

cluster.scale(5)

All this does is apply a patch to the resource and modify the spec.worker.replicas value to be 5 and the controller handles the rest.

Ultimately our Python API is generating YAML and handing it to Kubernetes to action. Everything about our cluster is contained in that YAML. If we prefer we can write and store this YAML ourselves and manage our cluster entirely via kubectl.

If we put the above YAML example into a file called my-cluster.yaml we can create it like this. No Python necessary.

$ kubectl apply -f my-cluster.yaml

daskcluster.kubernetes.dask.org/my-cluster created

We can also scale our cluster with kubectl.

$ kubectl scale --replicas=5 daskworkergroup my-cluster-default

daskworkergroup.kubernetes.dask.org/my-cluster-default

This is extremely powerful for advanced users who want to integrate with existing Kubernetes tooling and really modify everything about their Dask cluster.

You can still construct a KubeCluster object in the future and point it to this existing cluster for convenience.

from dask.distributed import Client

from dask_kubernetes.operator import KubeCluster

cluster = KubeCluster.from_name("my-cluster")

cluster.scale(5)

client = Client(cluster)

Cascade deletion

Having a DaskCluster resource also makes deletion much more pleasant.

In the old implementation your local Python process would spawn a bunch of Pod resources along with supporting ones like Service and PodDisruptionBudget resources. It also had some teardown functionality that was either called directly or via a finalizer that deleted all of these resources when you are done.

One downside of this was that if something went wrong either due to a bug in dask-kubernetes or a more severe failure that caused the Python process to exit without calling finalizers you would be left with a ton of resources that you had to clean up manually. I expect some folks have a label based selector command stored in their snippet manager somewhere but most folks would do this cleanup manually.

With the new model the DaskCluster resource is set as the owner of all of the other resources spawned by the controller. This means we can take advantage of cascade deletion for our cleanup. Regardless of how you create your cluster or whether the initial Python process still exists you can just delete the DaskCluster resource and Kubernetes will know to automatically delete all of its children.

$ kubectl get daskcluster # Here we see our Dask cluster resource

NAME AGE

my-cluster 4m3s

$ kubectl get all -A -l dask.org/cluster-name=my-cluster # and all of its child resources

NAMESPACE NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

default pod/my-cluster-default-worker-22bd39e33a 1/1 Running 0 3m43s

default pod/my-cluster-default-worker-5f4f2c989a 1/1 Running 0 3m43s

default pod/my-cluster-default-worker-72418a589f 1/1 Running 0 3m43s

default pod/my-cluster-default-worker-9b00a4e1fd 1/1 Running 0 3m43s

default pod/my-cluster-default-worker-d6fc172526 1/1 Running 0 3m43s

default pod/my-cluster-scheduler 1/1 Running 0 4m21s

NAMESPACE NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE

default service/my-cluster-scheduler ClusterIP 10.96.33.67 <none> 8786/TCP,8787/TCP 4m21s

$ kubectl delete daskcluster my-cluster # We can delete the daskcluster resource

daskcluster.kubernetes.dask.org "my-cluster" deleted

$ kubectl get all -A -l dask.org/cluster-name=my-cluster # all of the children are removed

No resources found

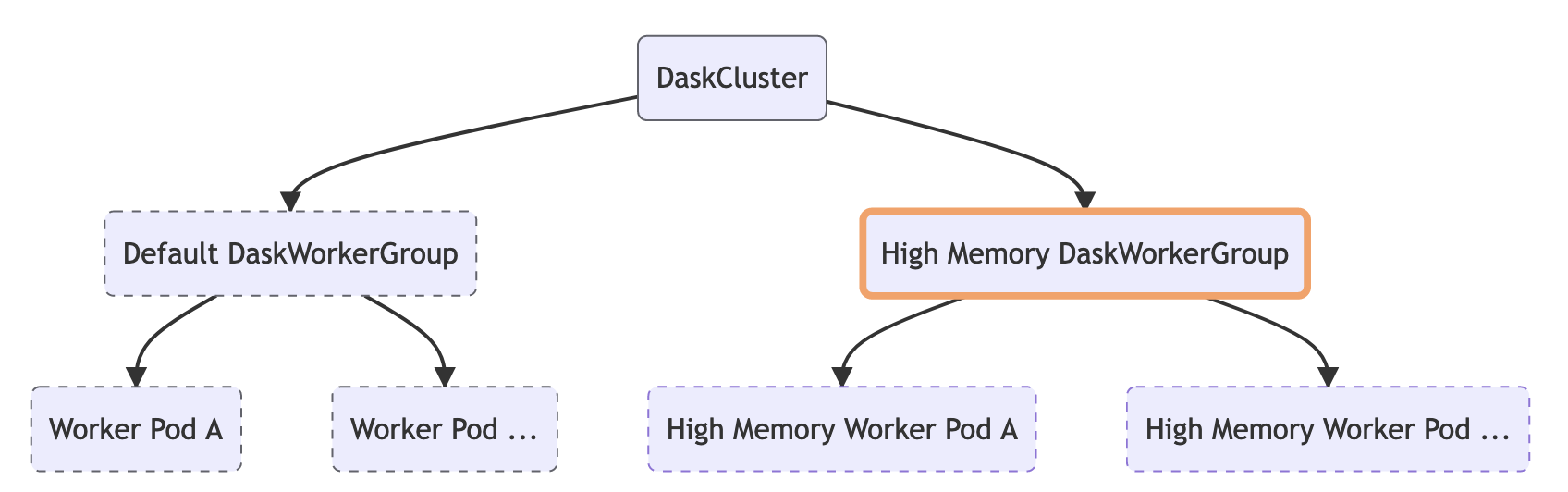

Multiple worker groups

We also took this opportunity to add support for multiple worker groups as a first class principle. Some workflows benefit from having a few workers in your cluster with some additional resources. This may be a couple of workers with much higher memory than the rest, or GPUs for accelerated compute. Using resource annotations you can steer certain tasks to those workers, so if you have a single step that creates a large amount of intermediate memory you can ensure that task ends up on a worker with enough memory.

By default when you create a DaskCluster resource it creates a single DaskWorkerGroup which in turn creates the worker Pod resources for our cluster. If you wish you can add more worker group resources yourself with different resource configurations.

Here is an example of creating a cluster with five workers that have 16GB of memory and two additional workers with 64GB of memory.

from dask_kubernetes.operator import KubeCluster

cluster = KubeCluster(name='foo',

n_workers=5,

resources={

"requests": {"memory": "16Gi"},

"limits": {"memory": "16Gi"}

})

cluster.add_worker_group(name="highmem",

n_workers=2,

resources={

"requests": {"memory": "64Gi"},

"limits": {"memory": "64Gi"}

})

Autoscaling

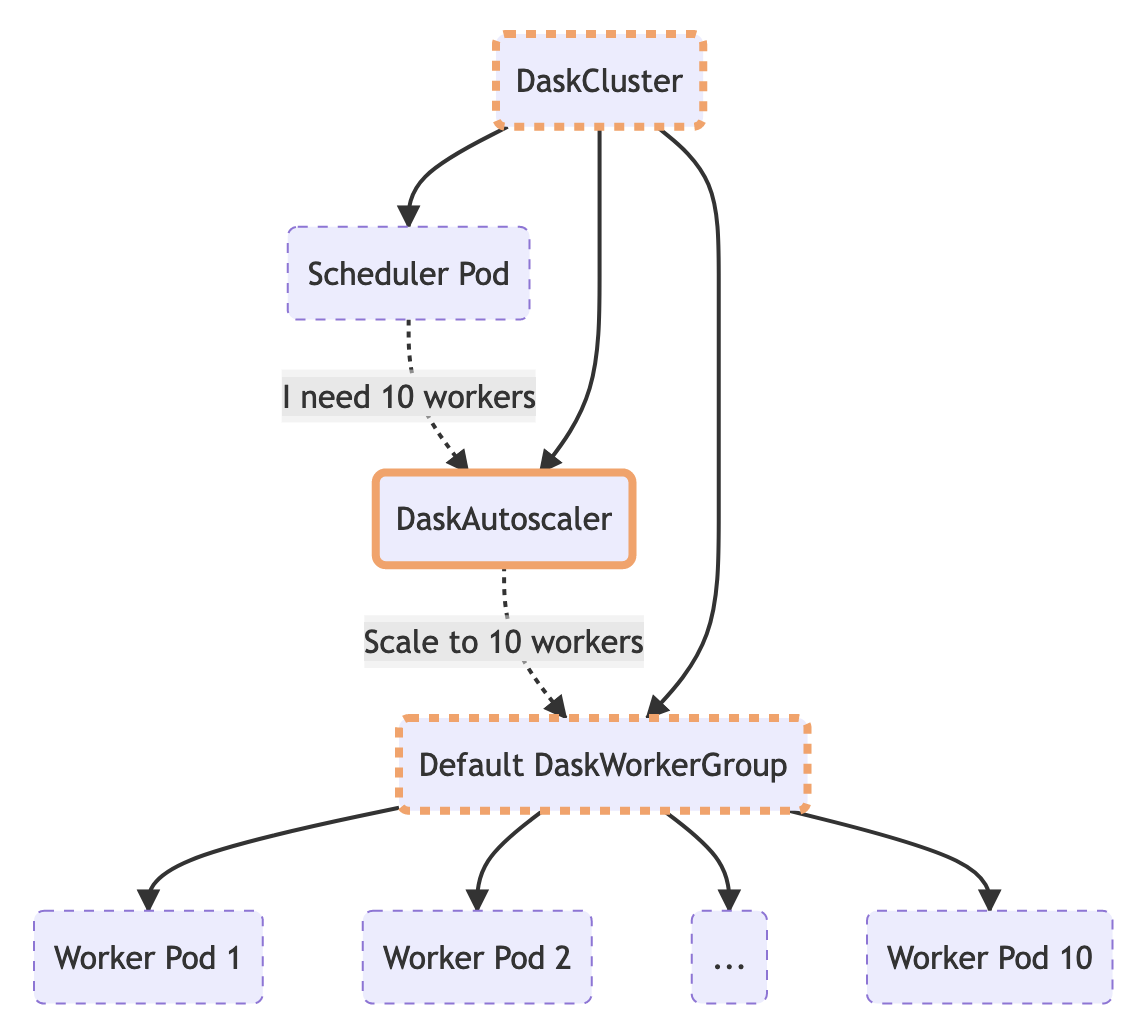

One of the much loved features of the classic implementation of KubeCluster was adaptive autoscaling. When enabled the KubeCluster object would regularly communicate with the scheduler and ask if it wanted to change the number of workers and then add/remove pods accordingly.

In the new implementation this logic has moved to the controller so the cluster can autoscale even when there is no KubeCluster object in existence.

The Python API remains the same so you can still use KubeCluster to put your cluster into adaptive mode.

from dask_kubernetes.operator import KubeCluster

cluster = KubeCluster(name="my-cluster", n_workers=5)

cluster.adapt(minimum=1, maximum=100)

This call creates a DaskAutoscaler resource which the controller sees and periodically takes action on by asking the scheduler how many workers it wants and updating the DaskWorkerGroup within the configured bounds.

apiVersion: kubernetes.dask.org/v1

kind: DaskAutoscaler

metadata:

name: my-cluster

spec:

cluster: my-cluster

minimum: 1

maximum: 100

Calling cluster.scale(5) will also delete this resource and set the number of workers back to 5.

DaskJob

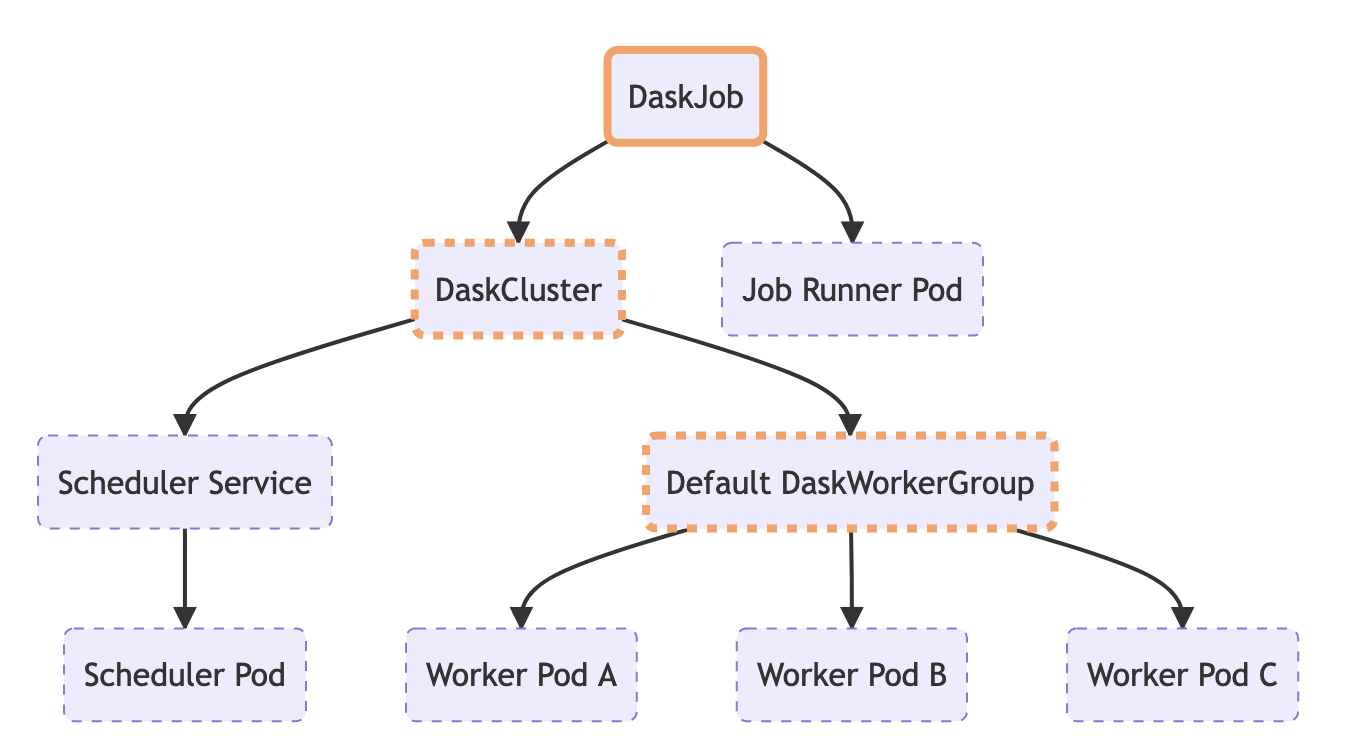

Having composable cluster resources also allows us to put together a new DaskJob resource.

Kubernetes has some built-in batch job style resources which ensure a Pod is run to completion one or more times. You can control how many times is should run and how many concurrent pods there should be. This is useful for fire-and-forget jobs that you want to process a specific workload.

The Dask Operator introduces a DaskJob resource which creates a DaskCluster alongside a single client Pod which it attempts to run to completion. If the Pod exits unhappily it will be restarted until it returns a 0 exit code, at which point the DaskCluster is automatically cleaned up.

The client Pod has all of the configuration for the DaskCluster injected at runtime via environment variables, this means your client code doesn’t need to know anything about how the Dask cluster was constructed it just connects and makes use of it. This allows for excellent separation of concerns between your business logic and your deployment tooling.

from dask.distributed import Client

# We don't need to tell the Client anything about the cluster as

# it will find everything it needs in the environment variables

client = Client()

# Do some work...

This new resource type is useful for some batch workflows, but also demonstrates how you could extend the Dask Operator with your own new resource types and hook them together with a controller plugin.

Extensibility and plugins

By moving to native Kubernetes resources and support for the YAML API power users can treat DaskCluster resources (or any of the new Dask resources) as building blocks in larger applications. One of Kubernetes’s superpowers is managing everything as composable resources that can be combined to create complex and flexible applications.

Does your Kubernetes cluster have an opinionated configuration with additional tools like Istio installed? Have you struggled in the last to integrate dask-kubernetes with your existing tooling because it relied on Python to create clusters?

It’s increasingly common for users to need additional resources to be created alongside their Dask cluster like Istio Gateway resources or cert-manager Certificate resources. Now that everything in dask-kubernetes uses custom resources users can mix and match resources from many different operators to construct their application.

If this isn’t enough you can also extend our custom controller. We built the controller with kopf primarily because the Dask community is strong in Python and less so in Golang (the most common way to build operators). It made sense to play into our strengths rather than using the most popular option.

This also means our users should be able to more easily modify the controller logic and we’ve included a plugin system that allows you to add extra logic rules by installing a custom package into the controller container image and registering them via entry points.

# Source for my_controller_plugin.plugin

import kopf

@kopf.on.create("service", labels={"dask.org/component": "scheduler"})

async def handle_scheduler_service_create(meta, new, namespace, logger, **kwargs):

# Do something here like create an Istio Gateway

# See https://kopf.readthedocs.io/en/stable/handlers for documentation on what is possible here

# pyproject.toml for my_controller_plugin

[option.entry_points]

dask_operator_plugin =

my_controller_plugin = my_controller_plugin.plugin

# Dockerfile

FROM ghcr.io/dask/dask-kubernetes-operator:2022.10.0

RUN pip install my-controller-plugin

That’s it, when the controller starts up it will also import all @kopf methods from modules listed in the dask_operator_plugin entry point alongside the core functionality.

Migrating

One caveat to switching to the operator model is that you need to install the CRDs and controller on your Kubernetes before you can start using it. While a small hurdle this is a break in the user experience compared to the classic implementation.

helm repo add dask https://helm.dask.org && helm repo update

kubectl create ns dask-operator

helm install --namespace dask-operator dask-operator dask/dask-kubernetes-operator

We also took this opportunity to make breaking changes to the constructor of KubeCluster to simplify usage for beginners or folks who are happy with the default options. By adopting the YAML API power users can tinker and tweak to their hearts content without having to modify the Python library, so it made sense to make the Python library simpler and more pleasant to use for the majority of users.

We made an explicit decision not to just replace the old KubeCluster with the new one in place because people’s code will just stop working if we did. Instead we are asking folks to read the migration guide and update your imports and construction code. Users of the classic cluster manager will start seeing a deprecation warning as of 2022.10.0 and at some point the classic implementation will be removed all together. If migrating is challenging to do quickly you can always pin your dask-kubernetes version, and from then on you are clearly not getting bug fixes or enhancements. But in all honesty those have been few and far between for the classic implementation lately anyway.

We are optimistic that the new cleaner implementation, faster cluster startup times and bucket of new features is enough to convince you that it’s worth the migration effort.

If you want some help migrating and the migration guide doesn’t cover your use case then don’t hesitate to reach out on the forum. We’ve also worked hard to ensure the new implementation has feature parity with the classic one, but if anything is missing or broken then please open an issue on GitHub.

blog comments powered by Disqus